Rain and the Will to Sprout

Once more I am the silent one who came out of the distance wrapped in cold rain and bells:

I owe to earth’s pure death the will to sprout.

Pablo Neruda

Neruda, P., & O’Daly, W. (2002). Winter garden. Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press.

Contrasts

Fragmented Memory

When autobiographical memory no longer constrains the self to (remembered) reality the result is distortion and fragmentation of the self.

memory: autobiographical, In: Oxford Companion to the Mind, 2nd ed.

I go out on the road alone

Alone I set out on the road;

The flinty path is sparkling in the mist;

The night is still. The desert harks to God,

And star with star converses.The vault is overwhelmed with solemn wonder

The earth in cobalt aura sleeps. . .

Why do I feel so pained and troubled?

What do I harbour: hope, regrets?I see no hope in years to come,

Have no regrets for things gone by.

All that I seek is peace and freedom!

To lose myself and sleep!But not the frozen slumber of the grave…

I’d like eternal sleep to leave

My life force dozing in my breast

Gently with my breath to rise and fall;By night and day, my hearing would be soothed

By voices sweet, singing to me of love.

And over me, forever green,

A dark oak tree would bend and rustle.

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov (1814-1841)

philadelphia association

On Disappointment

The progress of an individual through a fairly deliberate structured and emotionally stressful therapeutic situation such as this follows a typical course.

Initially the newcomer cautiously or boldly sets out to create the situation between himself and others in which he is comfortable and with which he is familiar. He tries to make the situation ‘viable’ to use the terminology of Whitaker and Leiberman. . . .

The expected new self does not suddenly emerge, however, and a period of depression and hopelessness may replace the initial enthusiasm. There is something of a negative transference now to the community which, as he sees it, offered everything and gave so little. . . .

(p. 207)

Whiteley, J.S. (1975). The large group as a medium for sociotherapy. In: L. Kreeger (Ed.) The Large group: dynamics and therapy. London: Constable.

Every human being on this earth is born with a tragedy, and it isn’t original sin. He’s born with the tragedy that he has to grow up. That he has to leave the nest, the security, and go out to do battle. He has to lose everything that is lovely and fight for a new loveliness of his own making, and it’s a tragedy. A lot of people don’t have the courage to do it.

–Helen Hayes

Open Dialogue

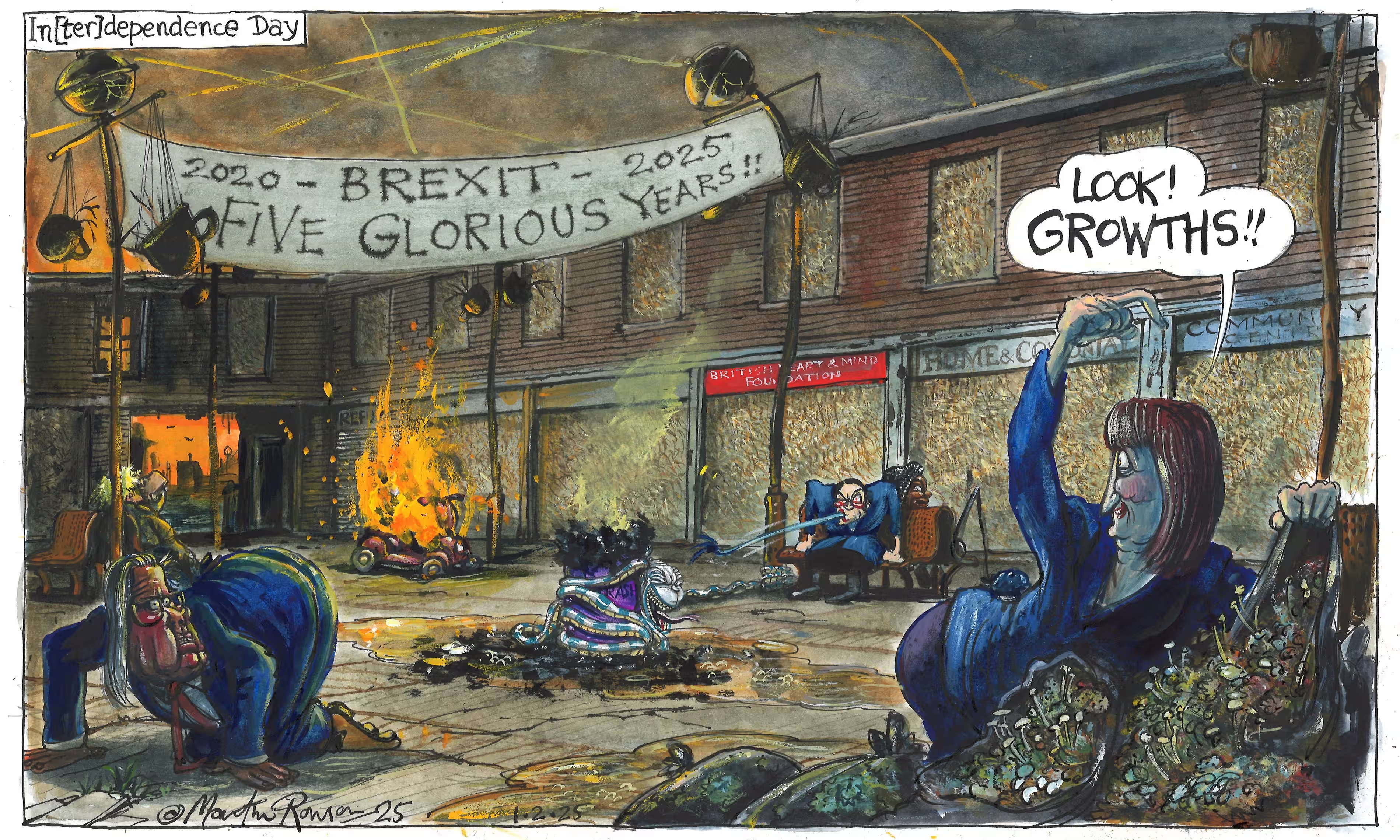

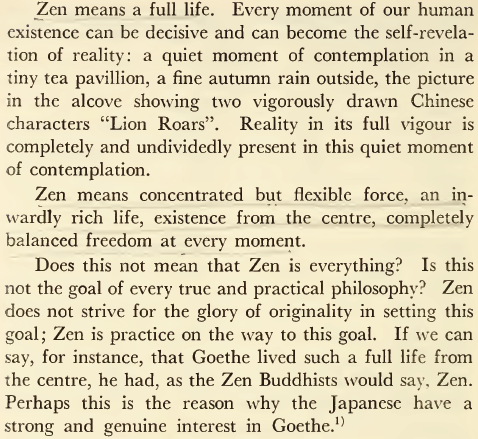

Zen

From Nishida (1966) Intelligibility and the Philosophy of Nothingness:

(p. 18)

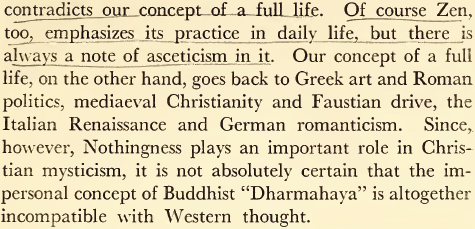

(p. 19)

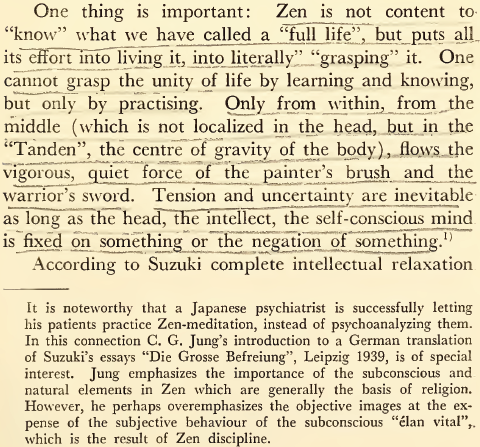

(p. 19/20)

(p. 29)

being motivated by a wisdom older than my thinking mind…

This is from a book titled ‘The Spell of the Sensuous’ by David Abraham, originally published in 1993. I read this in 2012 and felt enchanted. Nature, embodiment and contexts of being in general are interests of mine, and so much in this book resonated with me. Only recently, I rediscovered some notes I had jotted down, and I have decided to share three of my favourite quotations from the book:

It was as if my body in its actions was suddenly being motivated by a wisdom older than my thinking mind, as though it was held and moved by a logos, deeper than words, spoken by the Other’s body, the trees, and the stony ground on which we stood.

(p. 21)

… the intelligence that lurks in nonhuman nature, the ability that an alien form of sentience has to echo one’s own, to instill a reverberation in oneself that temporarily shatters habitual ways of seeing and feeling, leaving us open to a world all alive, awake and aware.

(p. 19)

For whatever we perceive is necessarily entwined with our own subjectivity, already blended with the dynamism of life and sentience. The living pulse of subjective experience cannot finally be stripped from the things that we study (in order to expose the pure unadulterated “objects”) without the things themselves losing all existence for us.

(p. 34)

David Abraham draws on the work of Merleau-Ponty and other philosophers / students of life, living and spirituality. I also feel reminded of two other books I love, Carl Jung’s ‘Memories, Dreams, Reflections’ and Mitchell Ginsberg’s ‘The inner palace: mirrors of psychospirituality in divine and sacred wisdom-traditions’.

Transactional Analysis

Losing trust in the world: Humiliation and its consequences

… acts of humiliation as a specific and often traumatic way of exercising power, with a set of consistently occurring elements and predictable consequences, including a loss of the ability to trust others. It is argued that these consequences are serious and long-lasting. The article makes a distinction between ‘shame’ as a state of mind and ‘humiliation’ as an act perpetrated against a person or group. The interplay between humiliation and shame after a humiliating act is discussed. . . .

I have loved the principle of beauty in all things

“If I should die,” said I to myself, “I have left no immortal work behind me — nothing to make my friends proud of my memory — but I have loved the principle of beauty in all things, and if I had had time I would have made myself remembered.”

John Keats to Fanny Brawne (c. February 1820).

love powerfully

Every morning

I shall concern myself anew about the boundary

Between the love-deed-Yes and the power-deed-No

And pressing forward honor reality.We cannot avoid

Using power,

Cannot escape the compulsion

To afflict the world,

So let us, cautious in diction

And mighty in contradiction,

Love powerfully.

Power and Love (1926)

mauvaises herbes

French for ‘weeds’ (in a flower bed), a combination of [and etymologically originating from] mauvaise [Latin malifātius, from malum (“bad”) + fatum (“fate”), i.e. bad, wrong, incorrect] and herbe [from Proto-Indo-European *gʰreH₁- “to grow, become green”]; considered here as a metaphor for some individuals’ sense of self, which often seems to me to be biased towards ‘negative’ or undesired aspects of self that are somehow undeserving of others or need to be got rid of. Whilst probably fitting in some respects, as weeds do drain other plants of nutrients and light, they also have many beneficial effects on surrounding plants and organisms in the ecosystem.

capacity to imagine

“Atrophy of the capacity to imagine is the breeding ground for self-inflicted misery. When old mythologies are corrupt and dysfunctional, one solution is to replace the ideas they symbolised by demonstrating their falseness, using the rationality of science. But for the psyche, the weakening of imagination is a trauma because what is lost in the imaginal realm can only be replaced by images, not by abstract concepts. Joy is a better teacher than pain – always” (p. 196).

Paris, G. (2007). Wisdom of the psyche. London: Routledge.

Being and Nothingness

Sara Cox shared something quite profound(ly human) during her show today- as she does. Might she have read Sartre’s Being and Nothingness?:

… like the, the sort of DJ anxiety dream that I have is that I’m pushing buttons and there is no music playing, and I’m turning me mic up, and, like, the microphone is not working and people can just hear silence [pause] and they can’t hear me –do you know what I mean– if people can’t hear me talk [pause, whispers:] I have nothing [pause], do you know what I mean, it’s all I have…

"I should like to bury something precious in every place where I’ve been happy and then, when I was old and ugly and miserable, I could come back and dig it up and remember…"

“But I was in search of love in those days, and I went full of curiosity and the faint, unrecognized apprehension that here, at last, I should find that low door in the wall, which others, I knew, had found before me, which opened on an enclosed and enchanted garden, which was somewhere, not overlooked by any window, in the heart of that grey city.”

“As I drove away and turned back in the car to take what promised to be my last view of the house, I felt that I was leaving part of myself behind, and that wherever I went afterwards I should feel the lack of it, and search for it hopelessly, as ghosts are said to do, frequenting the spots where they buried material treasures without which they cannot pay their way to the nether world.”

(Brideshead Revisited, The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder, Evelyn Waugh, 1945)

Sun Street Closed

Not depressed, just sad, lonely or unhappy

Excellent article in the BBC News Magazine:

Is sad so bad?

Cases of depression have grown around the world. But while awareness of the illness has helped lift the stigma it once attracted, have we lost touch with the importance of just feeling sad, asks Mary Kenny.

Immunology 2.0: brain, gut? – The Scientist

In order to progress, should the field of immunology look to other organ systems such as the brain and gut, or should it focus its efforts on all that remains unknown about the immune system itself? …

Read more: Immunology 2.0: brain, gut? – The Scientist – Magazine of the Life Sciences

Trauma and Human Existence

Robert D. Stolorow’s book Trauma and Human Existence is well worth a read, and I have decided to quote my favourite passages below:

One consequence of developmental trauma, relationally conceived, is that affect states take on enduring, crushing meanings. From recurring experiences of malattunement, the child acquires the unconscious conviction that unmet developmental yearnings and reactive painful feeling states are manifestations of a loathsome defect or of an inherent inner badness. A defensive self-ideal is often established, representing a self-image purified of the offending affect states that were perceived to be unwelcome or damaging to caregivers. Living up to this affectively purified ideal becomes a central requirement for maintaining harmonious ties to others and for upholding self-esteem. Thereafter, the emergence of prohibited affect is experienced as a failure to embody the required ideal—an exposure of the underlying essential defectiveness or badness—and is accompanied by feelings of isolation, shame, and self-loathing.

In the psychoanalytic situation, qualities or activities of the analyst that lend themselves to being interpreted according to such unconscious meanings of affect confirm the patient’s expectations in the transference that emerging feeling states will be met with disgust, disdain, disinterest, alarm, hostility, withdrawal, exploitation, and the like or that they will damage the analyst and destroy the therapeutic bond. Such transference expectations, unwittingly confirmed by the analyst are a powerful source of resistance to the experience and articulation of affect. Intractable repetitive transferences and resistances can be grasped, from this perspective, as rigidly stable “attractor states” (Thelen & Smith, 1994) of the patient-analyst system. In these states the meanings of the analyst’s stance have become tightly coordinated with the patient’s grim expectations and fears, thereby exposing the patient repeatedly to threats of retraumatization. The focus on affect and its meanings contextualizes both transference and resistance.

A second consequence of developmental trauma is a severe constriction and narrowing of the horizons of emotional experiencing (Stolorow et al., 2002, chap. 3) so as to exclude whatever feels unacceptable, intolerable, or too dangerous in particular intersubjective contexts. (…).

(p. 4)

… I tried to understand and conceptualize the dreadful sense of estrangement and isolation that seems to me to be inherent to the experience of emotional trauma. I became aware that this sense of alienation and aloneness appears as a common theme in the trauma literature (e.g., Herman, 1992), and I was able to hear about it from many of my patients who had experienced severe traumatization. One such young man, who had suffered multiple losses of beloved family members during his childhood and adulthood, told me that the world was divided into two groups; the normals and the traumatized ones. There was no possibility, he said, for a normal ever to grasp the experience of a traumatized one. (…)

(…) Axiomatic for Gadamer (1975) is the proposition that all understanding involves interpretation. Interpretation, in turn, can only be from a perspective embedded in the historical matrix of the interpreter’s own traditions. Understanding, therefore, is always from a perspective whose horizons are delimited by the historicity of interpreter’s organizing principles, by the fabric of preconceptions that Gadmer calls “prejudice.” Gadamer illustrates his hermeneutical philosophy by applying it to the anthropological problem of attempting to understand an alien culture in which the forms of social life, the horizons of experience, are incommensurable with those of the investigator.

(…) In Gadamer’s terms, I was certain that the horizons of their experience could never encompass mine, and this conviction was the source of my alienation and solitude, of the unbridgeable gulf separating me from their understanding. It is not just that the traumatized ones and the normals live in different worlds; it is that these discrepant worlds are felt to be essentially and ineradicably incommensurable.

(p. 14/15)

(…) When a person says to a friend, “I’ll see you later” or a parent says to a child at bedtime, “I’ll see you in the morning,” these are statements, like delusions, whose validity is not open for discussion. Such absolutisms are the basis for a kind of naive realism and optimism that allow one to function in the world, experienced as stable and predictable. It is the essence of emotional trauma that it shatters these absolutisms, a catastrophic loss of innocence that permanently alters one’s sense of being-in-the-world. Massive deconstruction of the absolutisms of everyday life exposes the inescapable contingency of existence on a universe that is random and unpredictable and in which no safety or continuity of being can be assured. Trauma thereby exposes “the unbearable embeddedness of being” (Stolorow & Atwood, 1992, p. 22). As a result, the traumatized person cannot help but perceive aspects of existence that lie well outside the absolutized horizons of normal everydayness. It is in this sense that the worlds of traumatized persons are fundamentally incommensurable with those of others, the deep chasm in which an anguished sense of estrangement and solitude takes form. (…).

(p. 16)

Essentially Existential

I used the following excerpts from Irvin D. Yalom’s book Existential Psychotherapy as part of my study notes. I haven’t always made an effort to cite properly, but page numbers after each quotation should be accurate.

Yalom’s book has four parts or ultimate concerns of life:

DEATH

FREEDOM

ISOLATION

MEANINGLESSNESS

DEATH

Two comments:

I personally prefer concepts such as senescence and a cycle of life and death (e.g. the idea that plants transfer all nutrients into their seeds and then ‘die’), as opposed to the idea of a linear progression towards death and finality; death thereby being a part of the greater thing that is existence, or something rather than nothing.

How useful is the idea of primary death anxiety underlying everything- is it not as diffuse as any other anxiety and impossible to ‘become a concrete fear’?

Quotations:

Heidegger believed that there are two fundamental modes of existing in the world. (1) a state of forgetfulness of being or (2) a state of mindfulness of being.

When one lives in a state of forgetfulness of being, one lives in the world of things and immerses oneself in the everyday diversions of life: One is “leveled down,” absorbed in “idle chatter,” lost in the “they.” One surrenders oneself to the everyday world, to a concern about the way things are.

In the other state, the state of mindfulness of being, one marvels not about the way things are but that they are. To exist in this mode means to be continually aware of being. In this mode, which is often referred to as the “ontological mode” (from the Greek ontos, meaning “existence”), one remains mindful of being, not only mindful of the fragility of being but mindful too, of one’s responsibility for one’s own being. Since it is only in this ontological mode that one is in touch with one’s self creation, it is only here that one can grasp the power of change oneself.

(p. 30/31)

Kierkegaard was the first to make a clear distinction between fear and anxiety (dread); he contrasted fear that is fear of some thing with dread that is fear of no thing — “not a nothing with which the individual has nothing to do.” One dreads (or is anxious about) losing oneself and become nothingness. This anxiety cannot be located.

(p. 43)

The child’s equation of sleep and death is well known. The state of sleep is the child’s closest experience of being nonconscious and the only clue the child has to what it is like to be dead. (In Greek mythology, death, Thanatos, and sleep, Hypnos, were twin brothers.) This association has implications for sleep disorders, and many clinicians have suggested that death fear is an important factor in insomnia both for adults and children. Many children regard sleep as perilous.

(p. 95)

Empirical research demonstrates that the child is fearful when separated, but in no way demonstrates that separation anxiety is the primal anxiety from which death anxiety is derived. At a level prior to thought and language the child may experience the inchoate anxiety of nonbeing; and that anxiety, in the child as in the adult, seeks to become fear: it is, in the only “language” available to the older child, bound and transformed into separation anxiety. Developmentalists eschew the idea that a young child—say, before the age of thirty months—could experience death anxiety, because the child has little concept of a self that is separate from surrounding objects. But the same may be said about separation anxiety. What is it that the child experiences? Certainly not separation, because without a conception of self, the child cannot conceive of separation. What is it, after all, that is being separated from what?

(p. 102)

… one must distinguish between two meanings of “fundamental”: “basic” and “chronologically first.” Even were we to accept the argument that separation anxiety is chronologically the first anxiety, it would not follow that death anxiety “really” is fear of object loss. The most fundamental (basic) anxiety issues from the threat of loss of self; and if one fears object loss, one does so because loss of that object is a threat (or symbolizes a threat) to one’s survival.

(p. 103)

… Rosenzweig and Bray present[s] data that indicates that among schizophrenic patients, when compared with a normal population, with a manic-depressive sample, and with a general paretic sample, there is a significantly greater incidence of a sibling dying before a patient’s sixth year.

(p. 104)

Josephine Hilgard and Martha Newman studied psychiatric patients who had lost a parent early in life, and reported an intriguing finding (which they termed “anniversary reaction”): a significant correlation between a patient’s age at psychiatric hospitalization and his or her parent’s age at death. In other words, when a patient is hospitalized there is a greather-than-chance possibility that he or she will be the same age as his or her parent was when the latter died. For example, if a patient’s mother died at the age of thirty, the patient is “at risk” at the age of thirty. Furthermore, the patient’s oldest child is likely to be the same age as the patient was when the parent died.

(p. 106/7)

Psychopathology (in every system) is, by definition, an ineffective defensive mode. Even defensive maneuvers that successfully ward off severe anxiety, prevent growth and result in a constricted and unsatisfying life. Many existential theorists have commented on the high price exacted in the struggle to cope with death anxiety. Kierkegaard knew that man limited and diminished himself in order to avoid perception of the “terror, perdition and annihilation that dwell next door to any man.” Otto Rank described the neurotic as one “who refused the loan (life) in order to avoid the payment of debt (death).” Paul Tillich stated that “neurosis is the way of avoiding non-being by avoiding being.” Ernest Becker made a similar point when he wrote: “The irony of man’s condition is that the deepest need is to be free of the anxiety of death and annihilation; but it is life itself which awakens it and so we must shrink from being fully alive.” Robert Jay Lifton used the term “psychic numbing” to describe how the neurotic individual shields himself from death anxiety.

(p. 111)

… after his wife left him, he realized that he felt he existed only if he were loved: in a state of isolation he froze, much like a terrified animal, into a state of suspended animation—not living but not dying either.

(p. 114)

In a crude, sweeping way, the two defenses constitute a dialectic—two diametrically opposed modes of facing the human situation. The human being either fuses or separates, embeds or emerges. He affirms his autonomy by “standing out from nature” (as Rank put it), or seeks safety by merging with another force. Either he becomes his own father or he remains the eternal son. Surely this is what Fromm meant when he described man as either “longing for submission or lusting for power.”

(p. 116)

Rank felt that there is in the individual a primal fear that manifests itself sometimes as a fear of life, sometimes as fear of death. By “fear of life” Rank meant anxiety in the face of a “loss of connection with a greater whole.” The fear of life is the fear of having to face life as an isolated being, it is the fear of individuation, of “going forward,” of “standing out from nature.” Rank believed that the prototypical life fear was “birth,” the original trauma and the original separation. By “fear of death” Rank referred to the fear of extinction, of loss of individuality, of being dissolved again into the whole.

(p. 141)

Rank’s poles of fear correspond closely to the inherent limits of the defenses I have described: “Life anxiety” emerges from the defense of specialness: it is the price one pays for standing out, unshielded, from nature. “Death anxiety” is the toll of fusion: when one gives up autonomy, one loses oneself and suffers a type of death. Thus one oscillates, one goes in one direction until the anxiety outweighs the relief of the defense, and then one moves in the other direction.

(p. 142)

That is what Rank meant when he said that the neurotic refuses the loan of life to escape the debt of death: he buys himself free from the fear of death by daily partial self-destruction.

(p. 147)

Norman Brown in his extraordinary book, Life Against Death, makes a similar statement: “Only he who can affirm birth can affirm death… The horror of death is the horror of dying with unlived lives in our bodies.”

(p. 151)

“Though the physicality of death destroys an individual, the idea of death can save him.”

(p. 159)

The neurotic obliterates the present by trying to find past in the future. It is, of course paradoxical… that it is the person who will not “live” who is most terrified of dying.

(p. 161/2)

Death reminds us that existence cannot be postponed. And that there is still time for life. If one is fortunate enough to encounter his or her death and to experience life as the “possibility of possibility” (Kierkegaard) and to know death as the “impossibility of further possibility” (Heidegger), then one realizes that, as long as one lives, one has possiblity—one can alter one’s life until—but only until—the last moment. If, however, one dies tonight, then all of tomorrows’s intentions and promises die stillborn.

(p. 162)

Disidentification is an obvious and ancient mechanism of change— the transcendence of material and social accouterments has long been embodied in ascetic traditions—but is not so easily available for clinical use. It is the awareness of death that promotes a shift in perspective and makes it possible for an individual to distinguish between core and accessory: to reinvest one and to divest the other.

(p. 165)

[Nietzsche:] “What has become perfect, all that is ripe—wants to die. All that is unripe wants to live. All that suffers wants to live, that it may become ripe and joyous and longing—longing for what is further, higher, brighter.”

(p. 208)

[Searles:] “The patient cannot face death unless he is a whole person, yet he can become a truly whole person only by facing death.” (…) It is not necessary that one experience forty years of whole, integrated living to compensate for the previous forty years of shadow life. Tolstoy’s Ivan Ilyich, through his confrontation with death, arrived at an existential crisis and, with only a few days of life remaining, transformed himself and was able to flood, retrospectively, his entire life with meaning.

(p. 208)

The major strategy is to separate ancillary feelings of helplessness from the true helplessness that issues from facing one’s unalterable existential situation. (…) And, when all else seems beyond one’s control, one, even then, has the power to control one’s attitude towards one’s fate—to reconstrue what one cannot deny.

There are other component fears: the pain of dying, afterlife, the fear of the unknown, concern for one’s family, fear for one’s body, loneliness, regression. In achievement-oriented Western countries death is curiously equated with failure. Each of these component fears, examined separately and rationally, is less frightening than the entire gestalt. Each is an obviously disagreeable aspect of dying; yet neither separately nor in concert, do these fears need to elicit a catalysmic reaction. It is significant, however, that many patients, when asked to analyze their death terrors, find that they correspond to none of these but to something primitive and ineffable. In the adult unconscious dwells the young child’s irrational terror: death is experienced as an evil, cruel, mutilating force.

(p. 212)

FREEDOM

Heidegger referred to the individual as dasein (not as “I” or “one” or “ego” or a “human being”) for a specific reason: he wished always to emphasize the dual nature of human existence. The individual is “there” (da), but also he or she constitutes what is there. The ego is two-in-one: it is an empirical ego (an objective ego, something that is “there,” an object in the world) and a transcendental (constituting) ego which constitutes (that is, is “responsible” for) itself and the world. Responsibility viewed in this manner is inextricably linked to freedom. Unless the individual is free to constitute the world in any of a number of ways, then the concept of responsibility has no meaning. The universe is contingent; everything that is could have been reated differently. Sartre’s view of freedom is far-reaching: the human being is not only free but is doomed to freedom. Furthermore, freedom extends beyond being responsible for the world (that is, for imbuing the world with significance): one is also entirely responsible for one’s life, not only for one’s actions but for one’s failures to act.

(p. 220)

Our sense data tell us that the world is “there,” and that we enter and leave it. Yet, as Heidegger and Sartre suggest, appearances enter the service of denial: we constitute the world in such a way that it appears independent of our constitution. To constitute the world as an empirical world means to constitute it as something independent of ourselves.

To be taken in by any of these devices that allow us to flee from our freedom is to live “inauthentically” (Heidegger) or in “bad faith” (Sartre).

(p. 222)

A synonym for responsibility assumption is “life management.”

(p. 242)

[Fritz Perls:] As long as you fight a symptom, it will become worse. If you take responsibility for what you are doing to yourself, how you produce your sumptoms, how you produce your illness, how you produce your existence—the very moment you get in touch with yourself—growth begins, integration begins.

(…)

We hear the patient first depersonalize himself into “it” and then become the passive recipient of the vicissitudes of a capricious world. “I did this” becomes “It happened.” I find that I must interrupt people repeatedly, asking that they own themselves. We cannot work with what occurs somewhere else and happens to one. And so I ask that they find their way from “It’s a busy day” to “I keep myself busy,” from “It gets to be a long conversation” to “I talk a lot.” And so on.

(…)

[Perls sometimes used an “I take responsibility” structured exercise:]With each statement, we ask patients to use the phrase, “… and I take responsibility for it.” For example, “I am aware that I move my leg… and I take responsibility for it.” “My voice is very quiet… and I take responsibility for it.” “Now I don’t know what to say …and I take responsibility for not knowing.”

(p. 246)

We choose each of our symptoms, Perls felt; “unfinished” or unexpressed feelings find their way to the surface in self-destructive, unsatisfying expressions. (This is the source of the term “Gestalt” therapy. Perls attempted to help patients to complete their gestalts—their unfinished business, their blocked out awareness, their avoided responsibilities.) (…)

This approach to symptoms—asking the patient to produce or augment a symptom—is often an effective mode of facilitating responsibility awareness: by deliberately producing the symptom, in this instance a stammer, the individual becomes aware that the symptom is his, it is of his own creation. Though they have not conceptualized it in terms of responsibility assumption, several other therapists have simultaneously arrived at the same technique. Viktor Frankl, for example, describes a technique of “paradoxical intention” in which a patient is asked deliberately to increase a symptom, e it an anxiety attack, compulsive gambling, fear of heart attack, or binge eating. Don Jackson, Jay Haley, Milton Erickson, and Paul Watzlawick have all written on the same approach, which they label “symptom prescription.”

(p. 247/8)

…[he] was expecting the impossible. He did not merely want an opinion. He wanted much more: he wanted somebody else to take the responsibility of his decision. (…) a profound human paradox: we yearn for autonomy but recoil from autonomy’s inevitable consequence—isolation. [Helmuth] Kaiser called this paradox “mankind’s congenital achilles heel” and said that we would suffer enormously from it if we did not cover it over with some “magician’s trick,” some device to deny isolation. That “magician’s trick” is what Kaiser called the “universal symptom”—a mechanism of defense which denies isolation by softening one’s ego boundaries and fusing with another. Earlier I discussed fusion or merger as a defense against death anxiety in the description of man’s yearning for an ultimate rescuer. Kaiser reminds us that isolation, and (and though he does not explicitly make that point) the groundlessness beneath isolation, is a powerful instigator of one’s efforts to fuse with another.

(p. 251)

[On the assumption of personal responsibility:]

- Recognizing that life is at times unfair and unjust.

- Recognizing that ultimately there is no escape from some of life’s pain and death.

- Recognizing that no matter how close I get to other people, I must still face life alone.

- Facing the basic issues of my life and death, and thus living my life more honestly and being less caught up in trivialities.

- Learning that I must take ultimate responsibility for the way I live my life no matter how much guidance and support I get from others.

(p. 265)

It is an ancient idea that each human being has a unique set of potentials that yearn to be realized. Aristotle’s “entelechy” referred to the full realization of potentiality. The fourth cardinal sin, sloth, or accidie has been interpreted by many thinkers as “the sin of failing to do with one’s life all that one knows one can do.” It is an extremely popular concept in modern psychology and appears in the writings of almost every modern humanistic or existential theorist or therapist [Notably Buber, Murphy, Fromm, Buhler, Allport, Rogers, Jung, Maslow, and Horney]. Although it has been given many names (that is, “self-actualization,” “self-realization,” “self-development,” “development of potential,” “growth,” “autonomy,” and so on), the underlying concept is simple: each human being has an innate set of capacities and potentials and, furthermore, has a primordial knowledge of these potentials. One who fails to live as fully as one can, experiences a deep, powerful feeling which I refer to here as “existential guilt.”

(p. 279)

But how is one to find one’s potential? How does one recognize it when one meets it? How does one know when one has lost one’s way? Heidegger, Tillich, Maslog, and May would all answer in unison: “Through Guilt! Through Anxiety! Through the call of conscience!” There is general consensus among them thatexistential guilt is a positive constructive force, a guide calling oneself back to oneself. When patients told her that they did not know what they wanted, Horney often replied simply, “Have you ever thought of asking yourself?” In the center of one’s being one knows oneself. John Stuart Mill, in describing this multiplicity of selves, spoke of a fundamental, permanent self which he referred to as the “enduring I.” No one has said it better than Saint Augustine: “There is one within me who is more myself than my self.”

(p. 280)

(…) It is the mental agency that transforms awareness and knowledge into action, it is the bridge between desire and act. It is the mental state that precedes action (Aristotle). It is the mental “organ of the future”—just as memory is the mental organ of the past (Arendt). It is the power of spontaneously beginning a series of successive things (Kant). It is the seat of volition, the “responsible mover” within (Farber). It is the “decisive factor in translating equilibrium into a process of change… an act occurring between insight and action which is experienced as effort or determination” (Wheelis). It is responsibility assumption—as opposed to responsibility awareness. It is that part of the psychic structure that has “the capacity to make an implement choices” (Arieti). It is a force composed of both power and desire, the “trigger of effort,” the “mainspring of action.”

To this psychological construct we assign the label “will,” and to its function, “willing.”(…)

(p. 289/290)

Despite these many problems, no term other than “will” serves our purpose. The definitions of will that I cited earlier … are marvelously descriptive of the psychological construct appealed to by the psychotherapist. Many have noted the rich connotations of the word “will.” It conveys determination and commitment—“I will do it.” As a verb “will” connotes volition. As an auxiliary verb it designates the future tense. A last will and testament is one’s final effort to lunge into the future. Hannah Arendt’s felicitous phrase “the organ of the future” has particularly important implications for the therapist, because the future tense is the proper tense of psychotherapeutic change. Memory (“the organ of the past”) is concerned with objects; the will is concerned with projects; and, as I hope to demonstrate, effective psychotherapy must focus on patients’ project relationships as well as on their object relationships.

(p. 291)

The clinician’s goal is change (action); responsible action begins with the wish. One can only act for oneself if one has access to one’s desires. If one lacks that access and cannot wish, one cannot project into the future, and responsible volition dies stillborn. Once wish materializes, the process of willing is launched and is transformed finally into action. What shall we call this process of transformation? The process between wish and action entails commitment; it entails “putting myself on record (to myself) to endeavor to do it.” The happiest term seems to me to be “decision”—or, “choice,” … To decide means that action will follow. If no action occurs, then no true decision has been made. I wishing occurs without action, then there has been no genuine willing. (If action occurs without wishing, then, too, there is no “willing”; there is only impulsive activity.)

(p. 302/3)

One’s capacity to wish is automatically facilitated if one is helped to feel. Wishing requires feeling. If one’s wishes are based on something other than feelings—for example, on rational deliberation or moral imperatives—then they are no longer wishes but “shoulds” or “oughts,” and one is blocked from communicating with one’s real self.

(p. 305)

[Perls began with awareness and gradually worked toward “wish.”]

I am convinced that the awareness technique alone can produce valuable therapeutic results. If the therapist were limited in his work only to asking three questions, he would eventually achieve success with all but the most seriously disturbed of his patients. These three questions are “What are you doing?” “What do you feel?” “What do you want?”

(p. 308)

Once an individual fully experiences wish, he or she is faced with decision or choice. Decision is the bridge between wishing and action. To decide means to commit oneself to a course of action. If no action ensues, I believe that there has been no true decision but instead a flirting with decision, a type of failed resolve. (…)

William James, who thought deeply about how decisions are made, described five types of decision, only two of which, the first and the second, involve “willful” effort:

- Reasonable decision. We consider the arguments for an against a given course and settle on one alternative. A rational balancing of books; we make this decision with a perfect sense of being free.

- Willful decision. A willful and strenuous decision involving a sense of “inward effort.” A “slow, dead heave of the will.” This is a rare decision’; the great majority of human decisions are made without effort.

- Drifting decision.In this type there seems to be no paramount reason for either course of action. Either seems good, and we grow weary or frustrated at the decision. We make the decision by letting ourselves drift in a direction seemingly accidentally determined from without.

- Impulsive decision. We feel unable to decide and the determination seems as accidental as the third type. But it comes from within and not from without. We find ourselves acting automatically and often impulsively.

- Decision based on change of perspective. This decision often occurs suddenly and as a consequence of some important outer experience or inward change (for example, grief or fear) which results in an important change in perspective or a “change in heart.”

(p. 314/5)

… “Things fade: alternatives exclude.” I regard that priest’s message as deeply inspired. “Things fade is the underlying theme of the first section of this book, and “alternatives exclude” is one of the fundamental reasons that decisions are difficult. (…)

Decisions as a Boundary Experience. To be fully aware of one’s existential situation means that one becomes aware of self-creation. To be aware of the fact that one constitutes oneself, that there are no absolute external referents, that one assigns an arbitrary meaning to the world, means to become aware of one’s fundamental groundlessness.

Decision plunges one, of one permits it, into such awareness. Decision, especially an irreversible decision, is a boundary situation in the same way that awareness of “my death” is a boundary situation. Both act as a catalyst to shift one from the everyday attitude to the “ontological” attitude—that is, to a mode of being in which one is mindful of being. Although, as we learn from Heidegger, such a catalyst and such a shift are ultimately for the good and prerequisites for authentic existence, they also call forth anxiety. If one is not prepared, one develops modes of repressing decision just as one represses death.

(p. 318/9)

… one “owns” one’s feelings. It is equally important that one owns one’s decisions. A decision made by another is no decision at all: one is not likely to commit oneself to it; and even if one does, no change in the process of decision making has been effected—one will not generalize to the next decision.

(p. 331)

[Leverage-producing insights:]

- “Only I can change the world I have created.”

- “There is no danger in change.”

- “To get what I really want, I must change.”

- “I have the power to change.”

(p. 340/1)

ISOLATION

The word “exist” implies differentiation (“ex-ist” = “to stand out”). The process of growth, as Rank knew, is a process of separation, of becoming a separate being. The words of growth imply separateness: autonomy (self-governing), self-reliance, standing on one’s own feet, individuation, being one’s own person, independence. (…)

The tension inherent in this dilemma is, in Kaiser’s term, the human being’s “universal conflict.” “Becoming an individual entails a complete, a fundamental, an eternal and insurmountable isolation.” (…)

To relinquish a state of interpersonal fusion means to encounter existential isolation with all its dread and powerlessness. The dilemma of fusion-isolation—or, as it is commonly referred to, attachment-separation—is the major existential developmental task. This is what Otto Rank meant when he emphasized the importance of birth trauma. To Rank, birth was symbolic of all emergence of embeddedness, what the child fears is life itself.

(p. 361/2)

(…) We will not relate to others with a full sense of them as like ourselves, as sentient beings, also alone, also frightened, also carving out a world of at-homeness from the paste of things. We behave toward other beings as toward tools or equipment. The other, now no longer an “other” but an “it,” is placed there, within one’s circle of the world, for a function. The fundamental function, of course is isolation denial, but awareness of this function is too close to the lurking terror. Greater concealment is needed; metafunctions emerge; and we constitute relationships that provide a product (for example, power, fusion, protection, greatness, or adoration) that in turn serves to deny isolation.

(p. 363)

… characteristics of a mature, need-free relationship…

- To care for another means to relate in a selfless way: one lets go of self-consciousness and self-awareness; one relates without the overarching thought, What does he think of me? or, What’s in it for me? One does not look for praise adoration, sexual release, power, money. One relates in the moment solely to the other person: there must be no third party, actual or imagined, observing the encounter. In other words, one must relate with one’s whole being: if part of oneself is elsewhere—for example, studying the effect that the relationship will have upon some third person—then to that extent one has failed to relate.

- To care for another individual means to know and to experience the other as fully as possible. If one relates selflessly, one is free to experience all parts of the other rather than the part that serves some utilitarian purpose. One extends oneself into the other, recognising the other as sentient being who has also constituted a world about himself or herself.

- To care for another means to care about the being and the growth of the other. With one’s full knowledge, gleaned from genuine listening, one endeavors to help the other become fully alive in the moment of the encounter.

- Caring is active. Mature love is loving, not being loved. One gives lovingly to the other; one does not “fall for” the other.

- Caring is one’s way of being in the world; it is not an exclusive, elusive magical connection with one particular person.

- Mature caring flows out of one’s richness, not out of one’s poverty—out of growth, not out of need. One does not love because one needs the other to exist, to be whole, to escape overwhelming loneliness. One who loves maturely has met these needs at other times, on other ways, not the least of which was the maternal love which flowed toward one in the early phases of life. Past loving then, is the source of strength; current loving is the result of strength.

- Caring is reciprocal. To the extent one truly “turns toward the other,” one is altered. To the extent one brings the other to life, one also becomes more fully alive.

- Mature caring is not without its rewards. One is altered, one is enriched, one is fulfilled, one’s existential loneliness is attenuated. Through caring one is cared for. Yet these rewards flow from genuine caring; they do not instigate it. To borrow from Frankl’s felicitous word play—the rewards ensue but cannot be pursued.

(p. 373)

There is, of course, a heavy overlap between the concept of escaping existential isolation through fusion and the concept of escaping the terror of death through belief and immersion of oneself in an ultimate rescuer. (…) Both concepts describe a mode of escaping anxiety by escaping individuation; in both one looks for solace outside the self. What differentiates the two is the impetus (isolation anxiety or death anxiety) and the ultimate goal (the search for ego boundary dissolution and merger or the search for a powerful intercessor). (…)

Fusion eliminates isolation in a radical fashion—by eliminating self-awareness. Blissful moments of merger are unreflective: the sense of self is lost. The individual cannot even say, “I have lost my sense of self,” because there is in fusion no separate “I” to say that. The wonderful thing about romantic love is that the questioning lonely “I” disappears into the “we.” “Love,” as Kent Bach comments, “is the answer when there is no question.” To lose self-consciousness is often comforting. Kierkegaard said: “With every increase in the degree of consciousness, and in proportion to that increase, the intensity of despair increases: the more consciousness, the more intense the dispair.”

(p. 380)

The conforming-fusion solution to isolation is undermined by the questions: What do I want? What do I feel? What is my goal in life? What do I have in me to express and fulfill?

(p. 381)

[Buber on an orientation he calls “reflexion” or not existing “between”:]

Many years I have wandered through the land of men, and have not yet reached an end of studying the varieties of the “erotic man.” There a lover stamps around and is in love only with his passion. There one is wearing his differentiated feelings like medal-ribbons. There one is enjoying the adventures of his own fascinating effect. There one is gazing enraptured at the spectacle of his own supposed surrender. There one is collecting excitement. There one is displaying his “power.” There one is preening himself with borrowed vitality. There one is delighted to exist simultaneously as himself and as an idol very unlike himself. There one is warming himself at the blaze of what has fallen his lot. There one is experimenting. And so on and on—all the manifold monologists with their mirrors, in the apartment of the most intimate dialogue!

(p. 384)

One, after all, does not find a relationship; one forms a relationship. (…) In such an inorganic approach to relationship, one views the other as an object with certain fixed properties and depletable resources. What one does not consider, Buber reminds us, in a genuine organic relationship there is reciprocity: there is no unchanging I observing (and measuring) the other; the I in the encounter is altered, and the other, the Thou, is altered as well. … as Fromm has taught us, this marketing approach to love makes no sense: engaging others always makes one richer not poorer.

(p. 387)

A full caring relationship is a relationship to another, not an extraneous figure from the past or the present. Transference, parataxic distortions, ulterior motives and goals—all must be swept away before an authentic relation with another can prevail.

(p. 391)

The characteristics of a need-free relationship provide the therapist with an ideal or horizon against which the patient’s interpersonal pathology is starkly silhouetted. Does, for example, the patient relate exclusively to those who can provide something for him? Is his love focused on receiving rather than giving? Does he attempt to know, in the fullest sense, the other person? How much of himself is held back? Does he genuinely listen to the other person? Does he use the other to relate to yet another—that is, how many people are in the room? Does he care about the growth of the other?

(p. 393)

… address existential isolation directly, to explore it, to plunge into his or her feelings of lostness and loneliness. One of the most fundamental facts that patients must dicover in therapy is that, though interpersonal encounter may temper existential isolation, in cannot eliminate it. (…) “Recognizing that no matter how close I get to other people, I must still face life alone“

(p. 397)

In The Art of Loving, Fromm wrote that “the ability to be alone is the condition for the ability to love,” and, in those days in the United States, before the 1960s and transcendental meditation, suggested modes of solitary concentration upon consciousness.

Clark Moustakas, in his essay on loneliness, made the same point:

The individual in being lonely, if let be, will realize himself in loneliness and create a bond or sense of fundamental relatedness with others. Loneliness rather than separating the individual or causing a break or division or self, expands the individual’s wholeness, perceptiveness, sensitivity and humanity.

(…) Similarly, Robert Hobson: “To be a human being means to be lonely. to go on becoming a person means exploring new modes or resting in our loneliness.”

(p. 398)

Earlier I said, “Psychotherapy is a cyclical process from isolation into relationship.” It is cyclical because the patient, in terror of existential isolation, relates deeply and meaningfully to the therapist and then, strengthened by this encounter, is led back again to a confrontation with existential isolation. The therapist, out of the depth of relationship, helps the patient to face isolation and to face his solitary responsibility for his own life—that it is the patient who has created his life predicament and that, alas, it is the patient, and no one else, who can alter it.

(p. 406)

Fromm, Maslow, and Buber all stressed that true caring for another means to care about the other’s growth and to bring something to life in the other. (…) Buber distinguishes two basic modes of affecting another’s attitude toward life. Either one tries to impose one’s attitude and opinions upon another (and in such a way that the other deems them to be his or her own views), or one attempts to help another discover his or her own dispositions and experience his or her own “actualizing forces.” The first approach Buber terms “imposition” and is the way of the propagandist. The second approach is “unfolding” and is the way of the educator and the therapist. Unfolding implies that one uncovers what was there all along. The very term “unfolding” has rich connotations and stands in sharp contrast to other terms depicting the therapeutic process—for example, “reconstruction,” “decondition,” “behavioral shaping,” “reparenting.”

(…) Heidegger, in analogous fashion, speaks of two different modes of caring or “solicitude.” [Heidegger distinguishes caring for things (“concern”) and caring for other daseins—taht is, constituting beings (“solicitude”).] One can “leap in” for another—a mode of relating similar to “imposition”—and thus relive another of the anxiety of facing existence (and, in so doing, limit the other to inauthentic existence). Or once can “leap ahead” (not a wholly satisfying term) and “liberate” the other by confronting the other with his or her existential situation

(p. 408)

I listen to a woman patient. She rambles on and on. She seems unattractive in every sense of the word—physically, intellectually, emotionally. She is irritating. She has many off-putting gestures. She is not talking to me; she is talking in front of me. Yet how can she talk to me if I am not here? My thoughts wander. My head groans. What time is it? How much longer to go? I suddenly rebuke myself. I give my mind a shake. Whenever I think of how much time remains in the hour, I know I am failing my patient. I try then to touch her with my thoughts. I try to understand why I avoid her. What is her world like at this moment? How is she experiencing the hour? How is she experiencing me? I ask her these very questions. I tell her that I have felt distant from her for the last several minutes. Has she felt the same way? We talk about that together and try to figure out why we lost contact with one another. Suddenly we are very close. She is no longer unattractive. I have much compassion for her person, for what she is, for what she might yet be. The clock races; the hour ends too soon.

(p. 415)

MEANINGLESSNESS

“Meaning” and “purpose” have quite different connotations. “Meaning” refers to sense, or coherence. It is a general term for what is intended to be expressed by something. A search for meaning implies a search for coherence. “Purpose” refers to intention, aim, function. (…)

What is the meaning of life? is an inquiry about cosmic meaning, about whether life in general or at least human life fits into some overall coherent pattern. What is the meaning of my life? is a different inquiry and refers to what some philosophers term “terrestrial meaning.” Terrestrial meaning (“the meaning of my life”) embraces purpose: one who possesses a sense of meaning experiences life as having some purpose or function to be fulfilled, some overriding goal or goals to which to apply oneself.

(p. 423)

Perhaps we can forgo the answer to the question, Why do we live? but it is not as easy to postpone the question, How shall we live? Modern secular humans face the task of finding some direction to life without an external beacon. How does one proceed to construct one’s own meaning—a meaning sturdy enough to support one’s life?

(p. 425)

[Secular activities that provide human beings with a sense of life purpose:]

- Altruism (p. 431f)

- Creativity (p. 435f)

- The Hedonistic Solution (p. 436f)

- Self-Actualization (p. 437f)

- Self-Transcendence (p. 439)

(p. 431ff)

What is important for both Camus and Sartre is that human beings recognize that one must invent one’s own meaning (rather than discover God’s or nature’s meaning) and then commit oneself fully to fulfilling that meaning. This requires that one be, as Gordon Allport put it, “half-sure and whole-hearted”—not an easy feat. Sartre’s ethic requires a leap into engagement. On this point most Western theological and atheistic existential systems agree: it is good and right to immerse oneself in the stream of life.

(p. 431)

Frankl—quite correctly, I believe—feels that the contemporary idealization of “self-expression” often, if made an end in itself, makes meaningful relationships impossible. The basic stuff of a loving relationship is not free self-expression (although that may be an important ingredient) but reaching outside of oneself and caring for the being of the other.

(p. 440)

The problem with a theory that posits some inbuilt drive (that is, the “drive to pleasure” or “tension reduction”) is that it is ultimately and devastatingly reductionistic. (…) Correspondingly, love, or altruism, or the search for truth, or beauty, is “nothing but” the expression of one or the other of the basic drives in duality theory. From this reductionistic point of view, as Frankl points out, “all cultural creations of humanity become actually by-products of the drive for personal satisfaction.”

(…) Frankl—along with many others (for example, Charlotte Buhler and Gordon Allport)—believes that homeostatic theory fails to explain many central aspects of human life. What the human being needs, Frankl says, “is not a tensionless state but rather a striving and struggling for some goal worthy of him.” “It is a constitutive characteristic of being human that it always points, and is directed, to something other than itself.”

Another major objection Frankl offers to a nontranscendent pleasure-principle view of human motiviation is that it is always self-defeating. The more one seeks happiness, the more it will elude one. This observation (termed the “hedonistic paradox” by many professional philosophers) led Frankl to say, “Happiness ensues; it cannot be pursued.”

(p. 443/4)

Frankl is careful to distinguish between drives (for example, sexual or aggressive) that push a person from within (or, as we generally experience it, from below) and meaning (and the values implicit in the meaning system) that pulls a person from without. The difference is between drive and strive. (…) “Striving” conveys a future orientation: we are pulled by what is to be, rather than pushed by relentless forces of past and present.

(p. 445)

[Frankl:]… The existential vacuum—or, as he sometimes terms it, “existential frustration”—is a common phenomenon and is characterized by the subjective state of boredom, apathy and emptiness. One feels cynical, lacks direction and questions the point of most of life’s activites. Some complain of a void and a vague discontent when the busy week is over (the “Sunday Neurosis”). Free time makes one aware of the fact that there is nothing one wants to do. (…)

If the patient develops, in addition to explicit feelings of meaninglessness, overt clinical neurotic symptomatology, then Frankl refers to the condition as an existential or “noogenic” neurosis. He posits a psychological horror vacui: when there is a distinct (existential) vacuum, symptoms will rush in to fill it. … alcoholism, depression, obsessionalism, delinquency, hyperinflation of sex, daredevilry. What differentiates noogenic neurosis from conventional psychoneurosis is that the symptoms are manifestations of a thwarted will to meaning. Behavioral patterns also reflect a crisis of meaninglessness. Modern man’s dilemma, Frankl states, is that one is not told what one must do, or any longer by tradition what one should do. Nor does one know what one wants to do. Two common behavioral reactions to this crisis of values are conformity (doing what others do) and submission to totalitarianism (doing what others wish).

(p. 449/450)

[Salvador Maddi; three forms of “existential sickness”]:

- Crusadism (also termed “adventurousness”): a powerful inclination to seek out and to dedicate oneself to dramatic and important causes.

- Nihilism: an active, pervasive proclivity to discredit activities purported by others to have meaning. The nihilist’s energy and behavior flow from despair…

- Vegetativeness: the most extreme degree of purposelessness. … one sinks into a severe state of aimlessness and apathy—a state that has widespread cognitive, affective, and behavioral expressions.

(p. 450f)

“What meaning is there in life?”—one learns that, often to a great extent, the question is primitive and contaminated.

For one thing, the question, as conventionally posed, assumes that there is a meaning to life that a particular patient is unable to locate. The question is in conflict with the existential view of the human being a meaning-giving subject. There is no pre-existing design, no purpose “out there.” How could there be one when each of us constitutes our own “out there”?

(p. 462)

Thus, one meaning of meaning is that it is an anxiety emollient: it comes into being to relieve the anxiety that comes from facing a life and a world without an ordained, comforting structure. There is yet another vital reason why we need meaning. Once a sense of meaning is developed, it gives birth to values—which, in turn, act synergistically to augment one’s sense of meaning.

(…)A standard anthropological definition of a value is: “A conception, explicit or implicit, distinctive of an individual or characteristic of a group, of the ‘desirable’ which influences the selection from available modes, means, and ends of action”

(p. 463f)

We too easily assume that death and meaning are entirely interdependent. If all is to perish, then what meaning can life have? If our solar system is to be ultimately incinerated, why strive for anything? Yet though death adds a dimension to meaning, meaning and death are not fused. If we were able to live forever, we would still be concerned about meaning. What if experiences do pass into memory and the ultimately fade? What relevance does that have for meaning? (…)

We are dealing with value judgments not with statements of fact. It is by no means an objective truth that nothing is important unless it goes on forever or eventually leads on to something else that persists forever. (…) As David Hume said in the eighteenth century, “It is impossible that there can be a progress ad infinitum, and that one thing can always be reason why another is desired. Something must be desirable on its own account and because of its immediate accord or agreement with human sentiment or affection.”

(p. 464f)

[Meaning of Life as a cultural artifact:] Suzuki suggests that this contrast illustrates Western and Eastern attitudes toward nature and, by implication, toward life. The Westerner is analytical and objective and attempts to understand nature by disecting and then subjugating and exploiting it. The Oriental is subjective, integrative, totalizing, and he attempts not to analyze and harness nature but to experience and harmonize with it. The contrast, then, is between a searching-action mode and a harmonizing-union one, and often is phrased in terms of “doing” versus “being.”

(p. 468)

The Western world has, thus, insidiously adopted a world view that there is a “point,” an outcome of all one’s endeavors. One strives for a goal. One’s efforts must have some end point, just as a sermon has a moral and a story, a satisfying conclusion. Everything is in preparation for something else. William Butler Yeats complained: “When I think of all the books I have read, wise words heard, anxieties given to parents …of hopes I have had, all life weighed in the balance of my own life seems to me a preparation for something that never happens.”

(p. 469)

(…) The Eastern world never assumes that there is a “point” to life, or that it is a problem to be solved; instead, life is a mystery to be lived. The Indian sage Bhaqway Shree Rajneesh says, “Existence has no goal. It is pure journey. The journey in life is so beautiful, who bothers for the destination?” Life just happens to be, and we just happen to be thrown into it.

(p. 470)

There is something inherently noxious in the process of stepping back too far from life. When we take ourselves out of life and become distant spectators, things cease to matter. From this vantage point, which philosophers refer to as the “galactic” or the “nebula’s-eye” view (or the “cosmic” or “global” perspective), we and our fellow creatures seem trivial and foolish. We become only one of countless life forms. Life’s activities seem absurd. The rich, experienced moments are lost in the great expanse of time. We sense that we are microscopic specks, and that all of life consumes but a flick of cosmic time.

(p. 478)

Meaning, like pleasure, must be pursued obliquely. A sense of meaningfulness is a by-product of engagement. Engagement does not logically refute the lethal questions raised by the galactic perspective, but it causes these questions not to matter. That is the meaning of Wittgenstein’s dictum: “The solution to the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of the problem.”

(p. 482)

A Confession

I recently read Tolstoy’s A Confession– all in one afternoon because it was so gripping! This is why I have decided to quote my favourite passages/sentences below (page numbers are from this edition). Before I simply copy down these quotations, I will attempt to provide some background information and a synopsis. You can skip all that jazz, of course ;o)

A Confession was first published in 1882 when Tolstoy was in his fifties (in Germany, I think, after it had been banned in Russia). By then, he had had a life of accomplishment: a large family and fortune, having published all his major fictional works- and yet he found himself to be profoundly unhappy. So much so, that he would nowadays probably be diagnosed as clinically depressed. He was searching for a meaning in his life that did not seem to offer any. This is why Tolstoy’s essay is a combination of his analysis of the meaning of life and an autobiographical testament of his struggle for life. Both of these characteristics, as well as Tolstoy’s literary skills, have made A Confession such an enjoyable and profound reading experience for me.

Tolstoy initially loses faith in the belief system he was brought up with and sees no meaning in life whatsoever. By means of an analysis of his life events/thoughts/emotions, and by conferring with what he calls ‘powerful minds’ (that is with influential thinkers of past times as well as philosophers of his day and age!) he then attempts to find an answer to his (and humankind’s) existential questions. By doing this, he finds his way back to a simple faith in God which he equates with life. He considers his faith free from all dogmatism, however, which might be one of the main reasons why he was excommunicated by the Russian Orthodox Church.

I find Tolstoy’s essay especially appealing because it seems to summarise much of the existentialist school of thought and indeed shows that we have not come up with any new answers and, more importantly, might never be able to. Another reason why I find Tolstoy’s conclusions intriguing is that his idea of living one’s life (i.e., in the here and now) equals faith which in turn equals the meaning of life, seems to tie in rather well with a promising component of contemporary psychotherapy, namely mindfulness. More about that in one of my next entries.

My favourite quotations from A Confession

… I was speaking exactly like a person who is in a boat being carried along by wind and waves and who when asked the most important and vital question, ‘Where should I steer?’ avoids answering by saying, ‘We are being carried somewhere.’ (p. 12)

I did not even wish to know the truth because I had guessed what it was. The truth was that life is meaningless. (p. 18)

It is only possible to go on living while you are intoxicated with life; once sober it is impossible not to see that it is all a mere trick, and a stupid trick! (p. 21)

… what will come of what I do today or tomorrow? What will come of my entire life? (p. 26)

It became apparent to me that to say that in the infinity of time and space everything is developing, becoming more perfect, complex and differentiated, is really to say nothing at all. They are all words without a meaning, for in the infinite there is no simple and complex, no before and after, and no better or worse. (p. 28)

These then are the straightforward answers given by human wisdom in reply to the questions of life:

‘The life of the body is evil and a lie. And since the annihilation of the life of the body is a blessing we must long for it,’ says Socrates.

‘Life is that which it should not be: evil. The transition into nothingness is the only thing sacred in life,’ says Schopenhauer.

‘Everything in the world, both folly and wisdom, richness and poverty, happiness and grief, all is vanity and emptiness. A man dies and nothing remains. This is absurd,’ says Solomon.

‘It is impossible to live in the consciousness that suffering, weakening, old age and death are inevitable; we must free ourselves from life, from all possibility of life,’ says Buddha.

And the very same thing said by these powerful minds has been said and thought by millions of people similar to them. And I too have thought and felt it. (p. 42f)

… I sensed anyway that if I wanted to live and to understand the meaning of life I must not seek it among those who have lost it and wish to kill themselves, but among the millions of people living and dead who have created life, and who carry the weight of our lives together with their own. (p. 53)

Clearly the solution to all the possible questions of life could not satisfy me because my question, however simple it may seem at first, involves a demand for an explanation of the finite by means of the infinite and vice versa.

I had asked: what meaning has life beyond time, beyond space and beyond cause? And I was answering the question: ‘What is the meaning of my life within time, space and cause?’ The result was that after long and laboured thought I could only answer: none. (p. 55)

It was now clear to me that in order for man to live he must either be unaware of the infinite, or he must have some explanation of the meaning of life by which the finite can be equated with the infinite. (p. 59)

The conviction that knowledge of the truth can only be found in life stirred me to doubt the worth of my own way of life. The thing that saved me was that I managed to tear myself away from my exclusive existence and see the true life of the simple working people, and realize that this alone is genuine life. I realized that if I wanted to understand life and its meaning I had to live a genuine life and not that of a parasite; and having accepted the meaning that is given to life by that real section of humanity who have become part of that genuine life, I had to try it out. (p. 71)

To know God and to live are one and the same thing. (p. 75)

The shore was God, the direction was tradition, and the oars were the freedom given to me to row towards the shore and unite with God. In this way the force of life rose up within me and I started to live once again. (p. 77)

I know that the explanation of all things, like the origin of all things, must remain a secret of eternity (p. 94)

How much can we change?

In his article “Experience-Dependent Epigenetic Modifications in the Central Nervous System” David Sweatt (2009) reviews molecular mechanisms of epigenetic effects (specifically, Histone acetylation and DNA methylation). These epigenetic mechanisms allow organisms to differentiate: although all cells contain (in principle) the same DNA sequence, only certain stretches of this sequence are transcribed/translated into the protein building-blocks that make up, for example, cells in the skin versus cells in the brain. How and if that happens appears to be governed by said mechanisms.

Sweatt (2009) reviews these epigenetic mechanisms and argues that they do not only play a central role in the development of organisms (particularly during so-called critical periods when organisms are very susceptible/able to change or acquire/lose a certain abilities) but also in seemingly less changing mature organism.

This potential change in mature organisms is very interesting as it may allow to help all those people affected by diseases of the brain, for example, which is what I am interested in. In theory, one would thus interfere with epigenetic mechanisms to bring about the desired change, for example the enhancement of memory or the loss of fear. In practice, some of these effects have so far been shown in animal models, which does not mean they can be as easily applied to humans or indeed extended to more complex cognitive functions of the brain. That is, the things that one can reliably infer an animal has learnt to fear or remember are few, the ways to ascertain this are even fewer, and how well any findings can be applied to the human brain is a contentious issue.

The question I asked myself after reading Sweatt’s (2009) article is how much ‘grown-up’ humans could possibly change, assuming that one can successfully interfere with epigenetic mechanisms in a desired manner?

The main strategy in psychiatric settings these days is to shape the environment in such a way as to potentially benefit the individual, hoping that this might bring about the desired (or indeed desperately needed change), which Sweatt (2009) suggests to be also mediated by epigenetic mechanisms. Examples include an enriched environment with lots of memory practice for people affected by dementia, or a low-stimulus, consistent and caring environment for many persons deemed to be affected by a mental illness.

The change that can be brought about by these environmental stimuli appears rather limited. Whilst cognitive decline may be slowed in dementia and coping abilities improved in mental illness, this is far from the dramatic and lasting(!) changes that have been shown to occur during developmental critical periods, for example, when organisms seem to be much more ‘malleable’.

What I am implying, then, is a rather pessimistic outlook on possible change effected in this way. The phenotype (including so-called mental disorders) that has been ingrained might be difficult to be reset sufficiently. My main reservation is that change brought about by interference with epigenetic mechanisms might affect or interact with the system as a whole and also lead to undesired side-effects (e.g. loss of certain maladaptive fears or compulsions may at the same time also affect adaptive behaviours). This is because the epigenetic mechanisms reviewed by Sweatt (2009) seem too fundamental to be used in a specific and localized way. The latter would assume a rather simple (biological) model of the disorder at hand (e.g. anxiety only being caused by a certain area of the brain), which we do not have at present.

This does not rule out the possibility, however, that the strategy of interfering with epigenetic mechanisms might not make the organisms slightly more susceptible to the desired change and thus accelerate the impact of (or in some cases enable) the influence of environmental change.

Nature strikes back

Yesterday I finally went for a run again. Major life events had brought on a cold that kept me from exercising. One of my favourite routes leads through the countryside and I had last been there in early spring.

Back then it had been snowing over night– a very rare event in this part of the country even in the dead of winter. The sun was shining and the snow not to last, so left early and had an awesome run through a fairy tale landscape full of glitter. I even met a couple walking their dog in shorts (the couple was wearing these and appeared to be out for some tanning). Trees and shrubs had been weighed down by the already melting snow which had transformed the downhill lane into into a narrow white tunnel.

This tunnel had turned into a green tangle of knee-high grass, shrubs and thorny undergrowth yesterday. To make matters worse, strong gusts of wind were pressing down shrubs that blocked my way along the overgrown path and had turned my usual route into a proper obstacle course. The trees were swaying in the wind and sounded like huge but soft, breaking waves on a beach. While I was running, crawling and wading through this awesome wilderness, I thought to myself: nature strikes back, I love it!